Overview

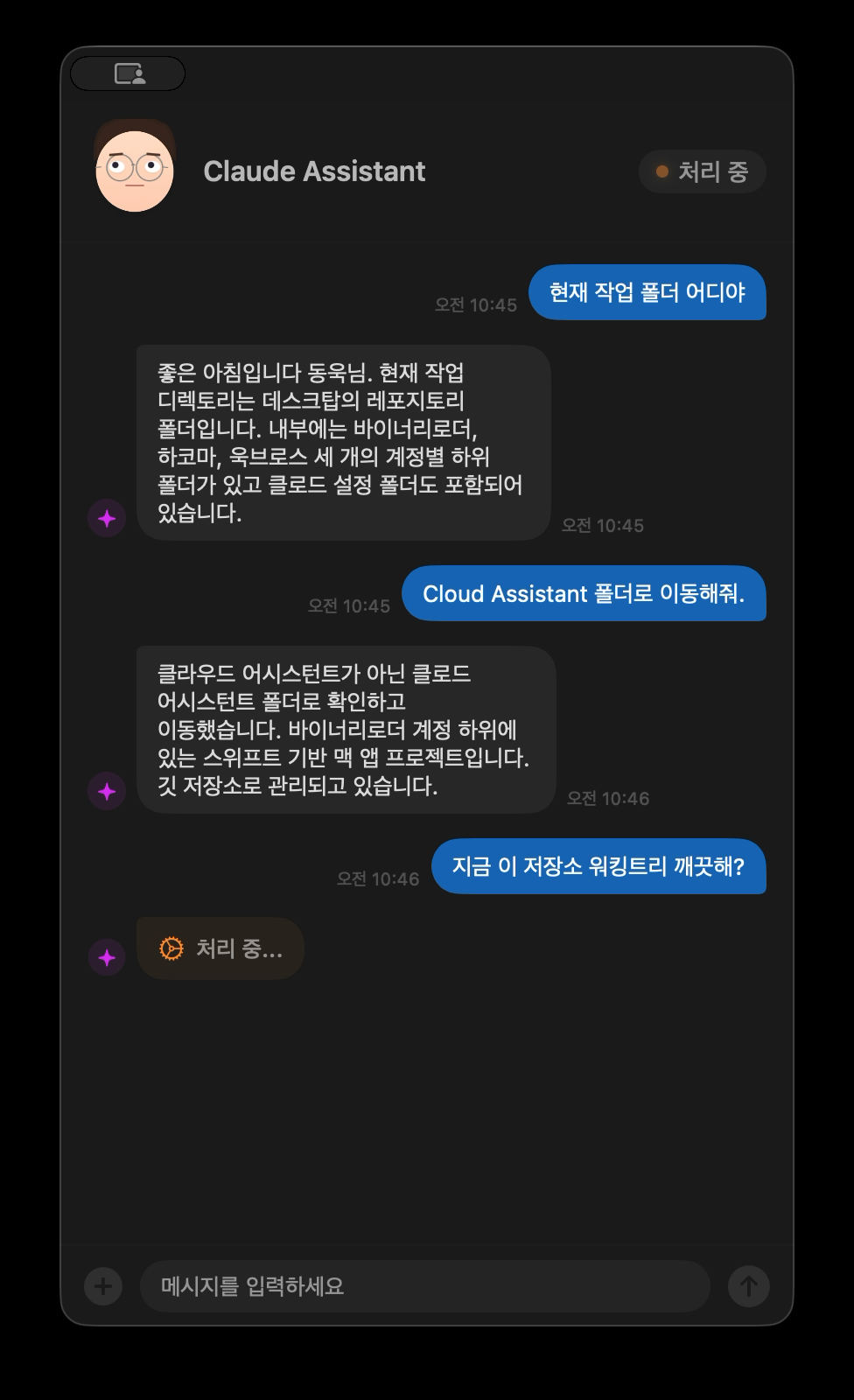

On a sleepless night I built a macOS assistant demo that relays Claude Code CLI’s input and output through voice. It just converts speech to text with whisper.cpp and reads responses back with Google Cloud TTS, but the process was fun.

How It Started

It was about 2 AM. I was trying to sleep but couldn’t. After tossing and turning, I gave up and opened my laptop. For a developer, a sleepless night is basically the start of a side project.

I’ve been using Claude Code practically all day long lately. It handles everything from code search to refactoring through text in the terminal, and a thought struck me. What if I could talk to it through a microphone and hear its responses through speakers?

Is it practical? Honestly, no. Code needs to be seen, and listening to terminal output through speakers is inefficient. But for quick commands like “What’s the current branch?” or “Open this file,” or check-ins like “Summarize the recent changes” — voice could be more convenient. Though if I’m being real, practicality wasn’t really the point. I just wanted to build it. There’s a certain joy in tinkering away at something like this alone at 2 AM.

I sketched out the architecture in my head while still in bed. Whisper for STT, Google Cloud for TTS, Claude Code as a CLI subprocess. The pieces seemed to fit together cleanly enough, so I jumped straight in.

Architecture

1. Overall Structure

The app is a native macOS application built with Swift Package Manager only, no Xcode project required. It uses SwiftUI and targets macOS 15 and above. There are no external Swift package dependencies. STT runs whisper.cpp as a subprocess and TTS calls the Google Cloud REST API, so no SPM dependencies were needed. Not having to deal with dependency management at 2 AM was a bonus, honestly.

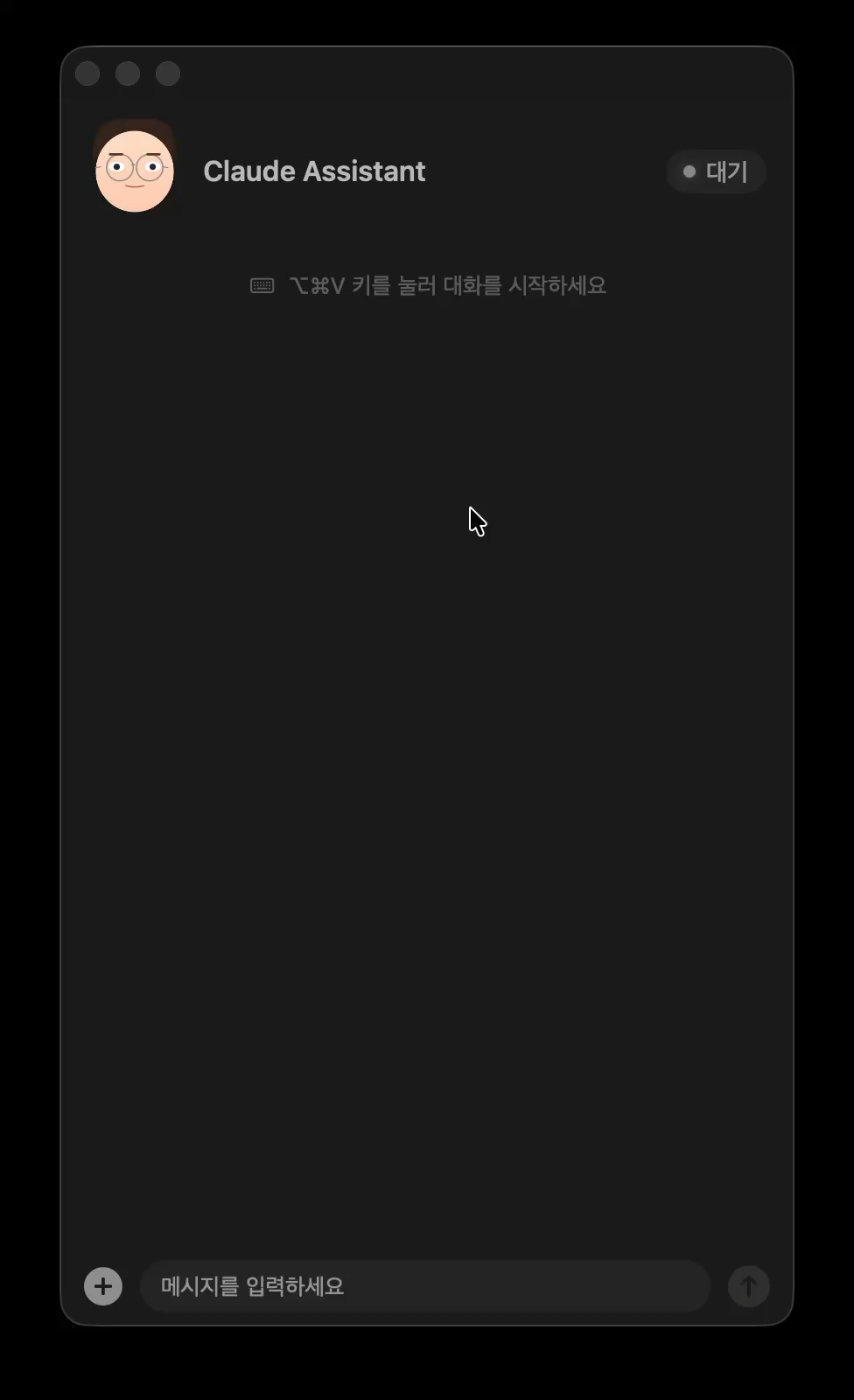

The app has two interfaces. Clicking the menu bar icon shows a usage dashboard in a popover, while pressing the global shortcut (⌥⌘V) opens a floating assistant panel. The dashboard is carried over from the Claude usage monitor I built previously, and the assistant panel is the new addition.

Usage dashboard shown when clicking the menu bar icon

Usage dashboard shown when clicking the menu bar icon

The service layer is abstracted through protocols: SpeechRecognizing, SpeechSynthesizing, ClaudeCodeExecuting, HotkeyListening, and PermissionChecking. Each protocol defines only the interface, with concrete implementations injected separately. For example, SpeechRecognizing defines just startListening() and stopListening(), while the actual Whisper integration lives in WhisperService. The idea is to limit the scope of changes when swapping in a different STT engine later.

ServiceContainer assembles all dependencies. TTS API keys and voice settings are read from UserDefaults and injected into each service at initialization. AppDelegate configures the ViewModels through this container, and the ViewModels connect to the Views. Admittedly overkill for a late-night demo project, but it’s nice knowing you only have to touch one place if something changes.

2. State Machine

The assistant’s behavior is managed by a finite state machine with five states.

From idle, pressing the hotkey transitions to listening. When the user finishes speaking, it moves to processing where Claude Code generates a response. Once ready, the speaking state plays the TTS audio, then returns to idle. Errors from any state transition to the error state, from which the user can retry or cancel back to idle.

I originally tried managing this with a handful of Bool flags — isListening, isProcessing, isSpeaking. But edge cases kept piling up: “What if another record request comes in while already recording?” “What if a new response arrives during TTS playback?” Eventually I switched to a proper state machine. The transition logic determines the next state from the current state and event, and invalid transitions just return nil and get ignored. This makes it much easier to track state even as the async flows grow complex.

One thing that tripped me up was the transition from processing to speaking. Claude Code response reception and TTS synthesis happen sequentially within the same Task, and I had logic that cancelled the activeTask on every state change — which killed the TTS synthesis too. I spent a good while at 3 AM debugging “why is there no sound?” before realizing this specific transition needed to preserve the existing Task as an exception.

Idle state — press the hotkey to start voice input

Idle state — press the hotkey to start voice input

3. Speech Input — whisper.cpp

For STT, I went with whisper.cpp. I tried Apple’s Speech framework first, but its Korean recognition for short sentences was disappointing. When it transcribed “현재 브랜치 알려줘” (tell me the current branch) as something completely garbled, I switched to Whisper immediately. The large-v3-turbo model delivered decent Korean recognition despite running locally. Working offline is a bonus.

The interaction model is Push-to-Talk. Holding down ⌥⌘V starts recording, and releasing it stops. I initially used NSEvent’s global monitor for hotkey detection, but it couldn’t properly capture keyDown/keyUp for modifier key combinations in a Push-to-Talk pattern. CGEvent tap is lower-level but can consume events (by returning nil), preventing key inputs from reaching other apps while the hotkey is held.

Recorded audio is captured by installing a tap on AVAudioEngine’s inputNode. Since Whisper requires mono input, the tap receives in single-channel format. Microphone selection in settings is handled by directly setting the CoreAudio AudioUnit property to change the input device.

The captured CAF file is converted to 16kHz 16-bit mono WAV using macOS’s built-in afconvert utility, as Whisper requires this format. After conversion, ffmpeg removes silence stretches longer than 3 seconds as preprocessing.

Whisper models have a notorious hallucination problem — they generate phantom sentences from silent input, things like “Thank you” or “Please subscribe and like.” Presumably from YouTube subtitle training data. It was a bit creepy the first time I saw it. Taming this required stacking multiple safeguards. Recordings shorter than 0.8 seconds or with peak audio levels below the threshold skip transcription entirely. If the file size after silence removal is under 10KB, it’s also skipped. The -nt (no timestamps) and -mc 0 (no context accumulation) flags prevent the model from being influenced by its own previous output. It took all of these layers before it finally worked reliably.

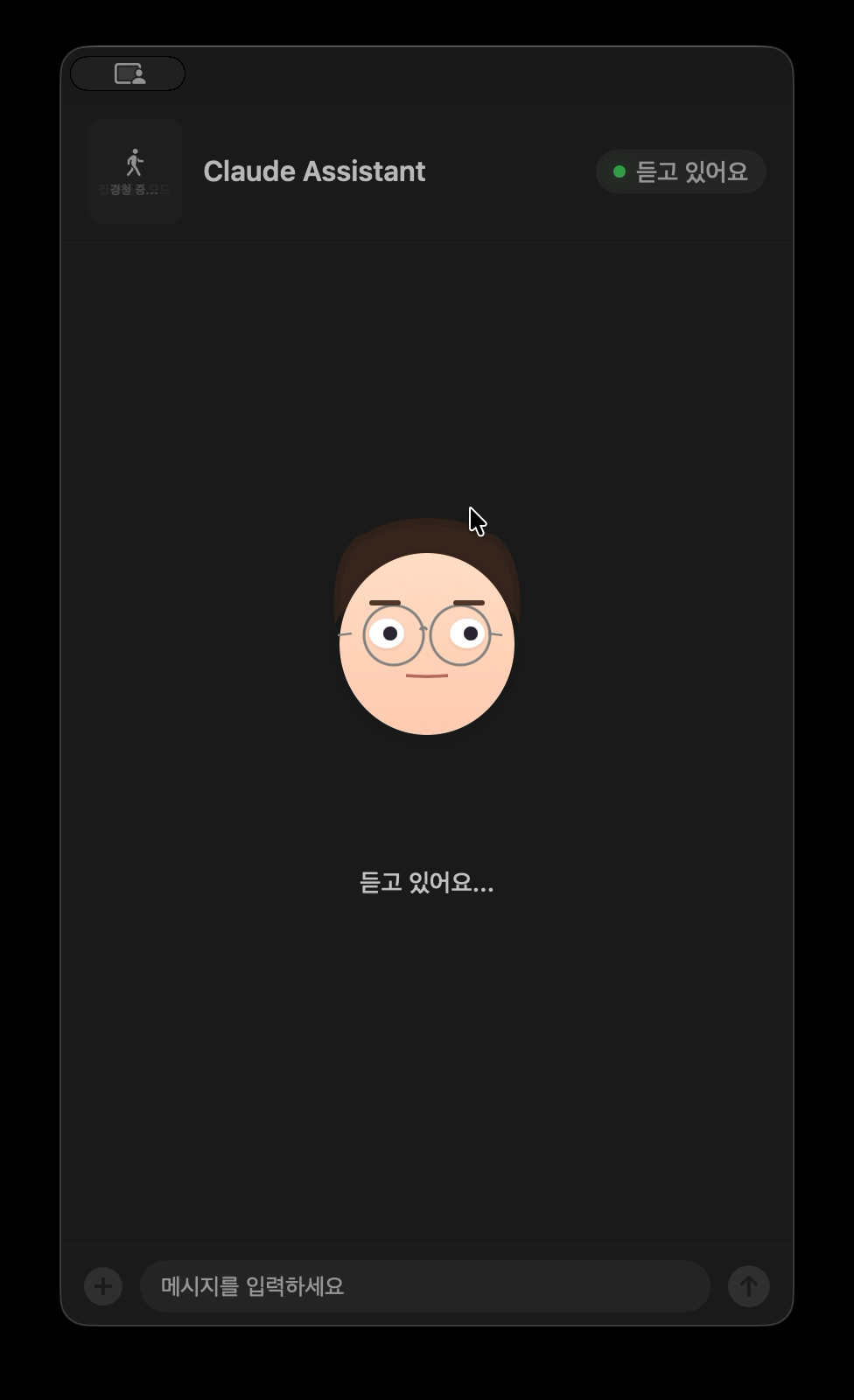

Listening — the avatar cups its ear

Listening — the avatar cups its ear

4. Speech Output — Google Cloud TTS

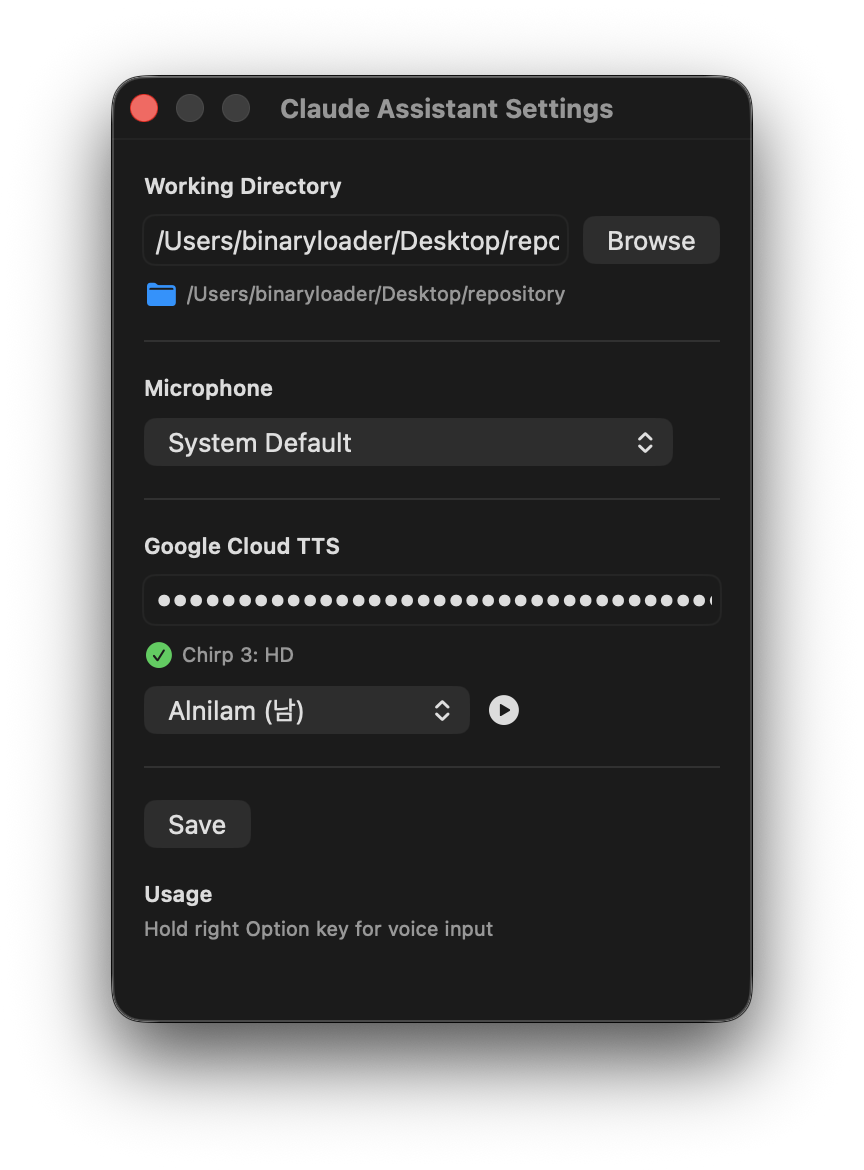

For TTS, I went with Google Cloud Text-to-Speech’s Chirp 3 HD model. Apple’s built-in TTS was too robotic for Korean. Chirp 3 HD, released by Google in 2025, has fairly natural intonation and breathing patterns. My first reaction was “oh, this is actually not bad.” Checking the pricing page, it offers a free tier of up to 1 million characters per month, so there was no cost barrier for a demo project.

The settings screen lets you choose from various voices and preview them. Chirp 3 HD offers diverse presets including male and female voices, each with unique names like Alnilam and Charon. API calls specify LINEAR16 (uncompressed PCM) encoding at 48kHz sample rate for the best possible audio quality.

Separating TTS text from Claude Code’s response was a surprisingly fun part. Claude’s responses are full of code blocks, file paths, and markdown syntax that would sound terrible read aloud. The system prompt instructs Claude to wrap voice-appropriate content in [TTS]...[/TTS] markers, rephrased in natural spoken language with minimal commas, phonetically written numbers, and no special characters. Tweaking these rules one by one took more effort than expected.

There was a notable trial-and-error moment. Initially, playing TTS audio immediately would clip the first ~0.5 seconds. “Good morning” came out as just “…orning.” The cause was macOS audio hardware needing initialization time. The fix was prepending 300 milliseconds of silence to the WAV data, which turned out to be trickier than it sounds. WAV files have a RIFF header containing the total file size and data chunk size. Inserting silence means manually patching these values at the byte level — offset 4 for RIFF size, offset 40 for data chunk size. To be fair, I didn’t actually count those byte offsets myself — Claude Code did. I was just grumbling “there’s no sound” and “the beginning is clipped” at 4 AM, and it figured out the header fix on its own. Hearing the audio play correctly for the first time was genuinely satisfying.

Google Cloud TTS settings — voice selection with preview

Google Cloud TTS settings — voice selection with preview

5. Avatar

The avatar is purely for fun. It serves zero functional purpose, but the beauty of a late-night project is having the freedom to spend time on useless things. It’s a round-faced, glasses-wearing character drawn in SwiftUI that changes expression based on the assistant’s state.

Expressions are defined through a FaceExpression struct — a combination of parameters like eye vertical scale (eyeScaleY), pupil position (pupilOffsetX/Y), eyebrow height and angle, mouth openness (mouthOpen), and smile amount (mouthSmile). In idle state, 14 different expressions using random combinations cycle every 1.8 seconds — subtle changes like slightly closed eyes, one raised eyebrow, or a shifted gaze.

In listening, the eyes widen (eyeScaleY: 1.15) and a hand-to-ear gesture appears, simply represented as an oval palm with three capsule-shaped fingers. During processing, pupils trace circles following sin/cos functions, and when tool activity includes “search,” they dart rapidly left and right. During code editing, the eyebrows draw together into a focused expression.

In speaking mode, the mouth opens and closes at random sizes (0–0.6) every 0.16 seconds. The mouth shape is a custom Shape called MouthShape, with openAmount and smile declared as AnimatableData so SwiftUI’s spring animations apply naturally.

I should have stopped there, but late-night energy is a thing. I added blinking at random 2.5–5.5 second intervals (eyelids close in 0.07s, open in 0.12s) and a breathing animation that subtly scales the body between 0.985 and 1.015. Nobody will ever notice, but this was the most fun part of the entire project.

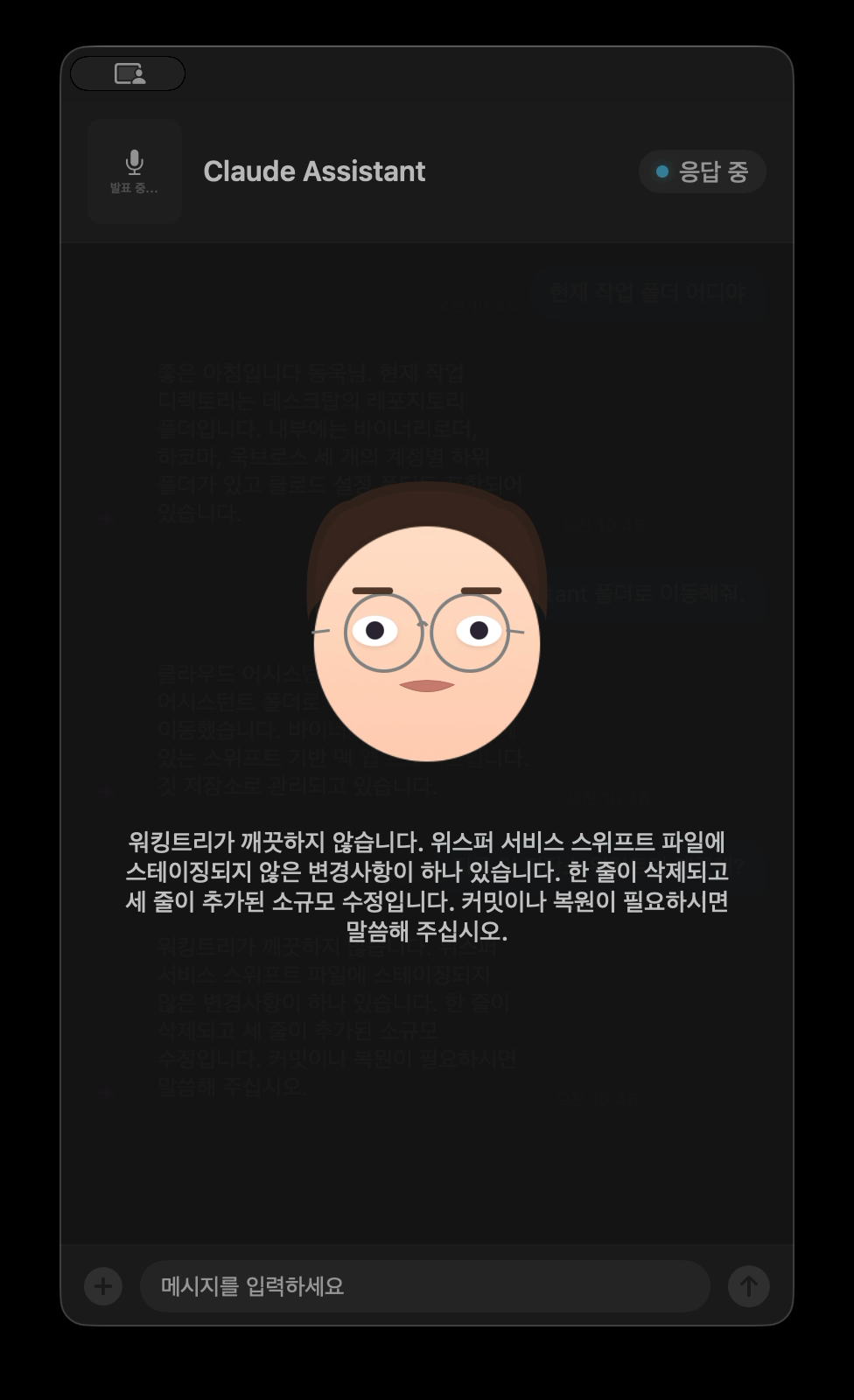

Speaking — the avatar moves its mouth while TTS text scrolls along

Speaking — the avatar moves its mouth while TTS text scrolls along

6. Claude Code Integration

The core mechanism is running Claude Code CLI as a subprocess. The --print flag runs it in non-interactive mode, --output-format stream-json provides streaming JSON responses, and --continue carries over previous conversation context for multi-turn dialogue.

Parsing the JSON streaming response was a surprisingly enjoyable task. Claude Code outputs one JSON object per line with type: "assistant" and a message.content array mixing text and tool_use blocks. Extracting tool names from tool_use blocks reveals what Claude Code is currently doing — “Running command…” for Bash, “Reading file…” for Read, “Searching code…” for Grep.

The system prompt features a persona with time-based greetings — “Working late, I see” for the small hours, “Good morning” in the morning — with concise, report-style responses and minimal apologies or over-explanations. Greetings only appear in the first turn. Hearing “Working late, I see” at 3 AM for the first time made me laugh out loud.

One bug ate up a good chunk of time. When running Claude Code CLI as a subprocess, inheriting the parent process’s environment variables directly causes issues. If CLAUDE_CODE_ENTRYPOINT and CLAUDECODE are set, Claude Code thinks it’s running inside another instance and behaves differently. I kept going “why does this work in the terminal but not in the app?” until I dumped the environment variables and finally spotted the culprit. These must be explicitly removed from the process environment for an independent session.

7. Chat UI

The assistant panel is a floating window using NSPanel. The .nonactivatingPanel style keeps the panel from stealing focus from the current app — ideal for having the assistant float alongside while coding. .canJoinAllSpaces and .fullScreenAuxiliary make it accessible from all desktop spaces and full-screen mode, and hidesOnDeactivate = false prevents it from disappearing when switching apps.

Chat messages are displayed in speech bubbles. User messages appear as right-aligned blue bubbles with white text, while assistant messages are left-aligned semi-transparent bubbles. UnevenRoundedRectangle reduces the corner radius on the tail side for a natural shape.

Text input is also supported. While voice handles most interactions, there are times when the environment is too quiet or longer text needs to be sent — the text field at the bottom allows direct input. Image attachment works too: selecting an image via NSOpenPanel includes the path in the message sent to Claude Code.

During processing, an indicator shows which tool Claude Code is currently using. The icon varies by type — magnifying glass for search, document for file reading, pencil for code editing, globe for web search.

Actual conversation — voice commands handle folder navigation and status checks

Actual conversation — voice commands handle folder navigation and status checks

Reflections

For a demo born from insomnia, it turned out more usable fun than expected. As an answer to “Can you put a voice on Claude Code?” — it’ll do.

In actual use, asking “What’s the current working directory?” by voice and hearing “The current working directory is the repository folder on your Desktop” through the speakers is pretty refreshing. Ask “Is the working tree clean?” and it checks the status and answers in conversational language. You can do the same in a terminal, but there’s a certain convenience in not needing to touch the keyboard.

The one downside is response latency. After a voice query, Claude Code needs time to analyze, call tools, and generate a response. Even simple questions can take anywhere from a few seconds to over ten, and that wait feels much longer through a voice interface.

Right now whisper.cpp, Google Cloud TTS, and Claude Code CLI are chained sequentially like a pipeline, so each stage’s latency stacks up directly. It’s just off-the-shelf components glued together, which makes you wonder if this is the best you can do. On the engineering side, streaming TTS that starts synthesis as soon as the first sentence is ready, or pre-initializing the audio session when entering the processing state to eliminate playback startup delay, could help. On the LLM side, routing simple queries like “What’s the current branch?” to a lighter model like Haiku, or having a voice-specific system prompt that distinguishes questions answerable without tool calls from those requiring analysis, are worth exploring. Caching frequently asked information like git status or the current directory locally and skipping the LLM call entirely is another option. I didn’t go this far for a demo, but even just streaming TTS alone would make a noticeable difference.

The most painful part was definitely Whisper hallucination. Add a safeguard, test it, find another pattern that breaks through, patch it again — rinse and repeat. The clipped first syllable in TTS also took a while to diagnose. Audio hardware initialization delay isn’t something you’d catch from logs alone, and the fix of prepending silence required byte-level WAV header surgery.

The avatar expressions, on the other hand, were the most useless yet most enjoyable part. Tweaking parameters and going “oh this one’s cute” or “nope, that’s creepy” alone in the dark — that’s how hours disappear at 3 AM.

What started at 2 AM went well past sunrise. “I should really sleep… wait, it’s already 10 AM?” Still, it was a pretty good time.

Leave a comment